"As the numbers of migrants attempting to cross the border between official ports of entry escalate rapidly, experts predict that more and more people will turn to human smuggling – unless Canada shores up its border enforcement."

Why human smuggling attempts are on the rise on the U.S.-Canada border

Akwesasne has long been a gaping hole in the U.S.-Canada border – exploited by smugglers to ship tobacco, guns and, most horrific, people.

Organized crime rings have targeted it for its strategic location, wedged between Quebec, Ontario and New York state. And sometimes, those who believe in its reputation as an undefended portal to a better life end up paying with their own lives.

As the numbers of migrants attempting to cross the border between official ports of entry escalate rapidly, experts predict that more and more people will turn to human smuggling – unless Canada shores up its border enforcement.

In late March, two migrant families – one from Romania and one from India – died in a failed smuggling attempt on the St. Lawrence River. But they were not the first.

In 2015, two men from India drowned and a third was rescued while attempting to be smuggled into the U.S. on the St. Lawrence in a Seadoo when it capsized. Last year, an Indian family died near Emerson, Man., in a failed attempt to cross into the U.S.

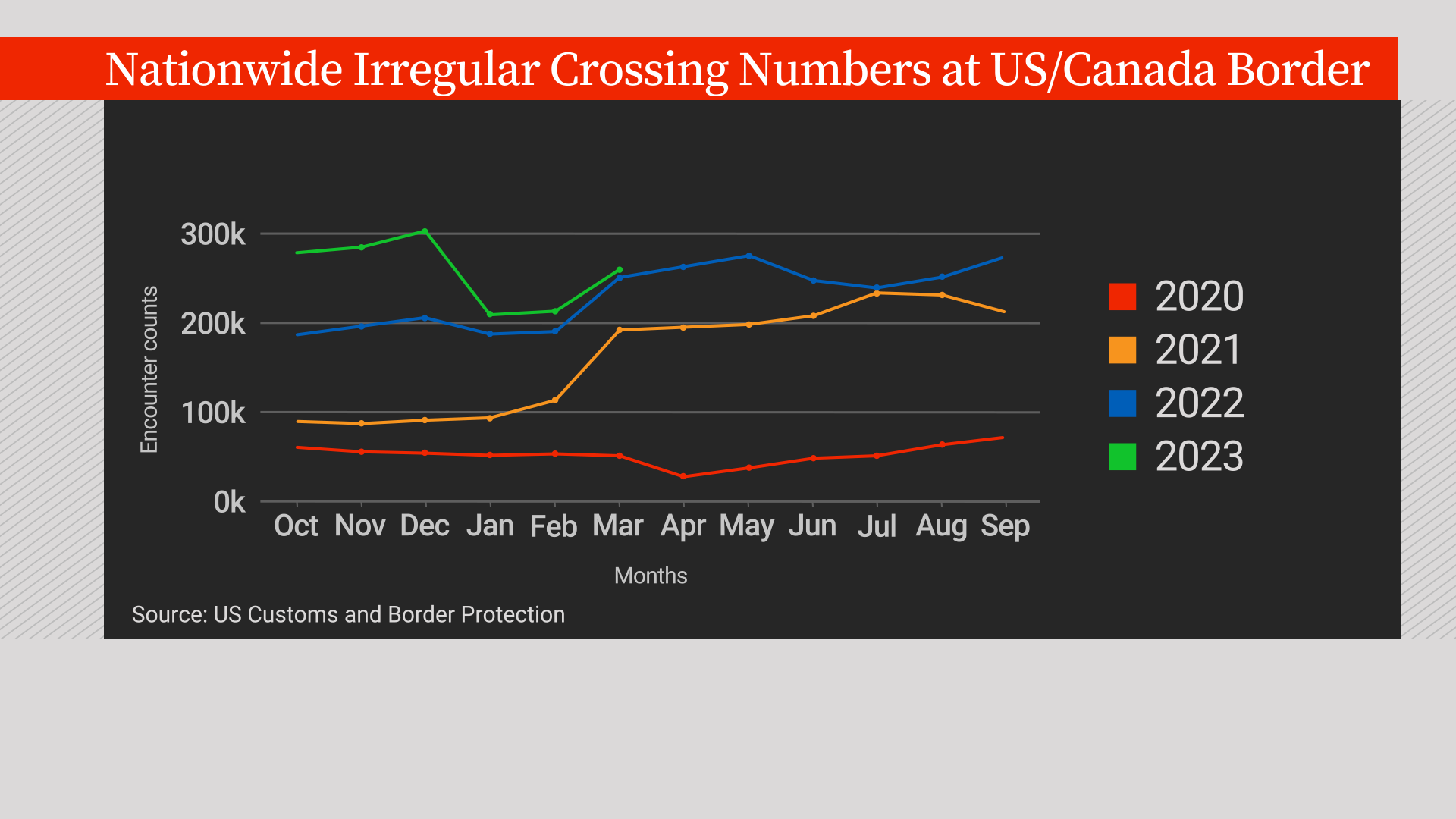

Across the 9,000-kilometre stretch of U.S.-Canada border, encounters with migrants are on the rise, statistics from U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) show.

In the year to March 2022, CBP officers recorded 109,535 attempts by migrants to cross into the U.S. Six months into the 2023 fiscal year, there have already been 84,555.

On the Canadian side, migrants typically leave from Cornwall, Ont., or nearby, boarding a boat helmed by a local. From there, it’s about a 15-minute trip to New York through the Mohawk Nation at Akwesasne First Nation – an Indigenous reserve split in half by the U.S. and Canadian border.

Cornwall and Akwesasne police, as well as U.S. authorities, are routinely apprehending migrants using smuggling “agencies” – a clandestine operation linking brokers in Toronto and Montreal to locals in Cornwall and Akwesasne to ferry them over the river to a better life.

Locals speak of the smuggling industry with an air of indifference. For many, it’s been going on so long, it’s become part of the fabric of the area.

“The town has become apathetic towards it,” the owner of a local cafe, who asked not to be named, says.

“There was a restaurant who was busted for it a few years ago, and people will say, ‘Sure, they were done for smuggling but, you know, they do good shawarma.’”

In 2015, provincial police broke up a gun trafficking ring in Cornwall that operated out of a shawarma restaurant directly across the street from a police station.

Experts have differing ideas on what Canada should do to secure its land borders.

Kelly Sundberg, a retired Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) officer and now Mount Royal University professor, says the current land border security system – run by the CBSA and the RCMP – is “inefficient,” and the RCMP must be booted off the job for it to improve.

“If we’re really serious about people smuggling … the CBSA needs to be really ramped up. It needs resources. And it needs to be held accountable,” he says.

But the people of Akwesasne would disagree. If they had jurisdictional control over their community, local historian and journalist Doug George-Kanentiio says, the people smuggling industry would be “stopped overnight.”

“We’d have a Mohawk militia out on those waters and we know we could stop this ourselves.”

But all agree on one point. With an increasing number of migrants heading for the border, and the recent closure of Quebec’s Roxham Road – once a key route for people hoping to apply for political asylum in Canada – people will put themselves in increasing danger for a shot at a better life.

The Swanton Sector’s human smuggling industry

The St. Lawrence River is a treacherous expanse of water, separating Canada from the U.S., and in parts, Quebec from Ontario. On its northern banks sits Cornwall, Ontario’s easternmost town – which, like Akwesasne, is deeply entrenched in the smuggling industry.

Two years before the shawarma restaurant was busted, the Cornwall Regional Task Force busted a massive marijuana ring operating in the area, arresting about 37 people.

Human smugglers are busted, too, from time to time. But they are usually arrested and charged in isolation while the system continues to operate in the background.

In 2018, 39-year-old Louie McDonald of Snye, Que., was found guilty at trial on two counts of manslaughter and a breach of a probation order related to smuggling after two Indian men drowned while he was ferrying them across the St. Lawrence River on his Seadoo in 2015. He was sentenced to 13 months and 25 days in jail.

A co-accused in the case, Jacob Wesley Martin from Hogansburg, N.Y., was due to stand trial in 2017 but instead crossed into Canada and was deemed a “fugitive,” according to U.S. court documents. Later, the RCMP arrested him on charges related to the case.

Global’s attempts to track him down via the RCMP, the Correctional Service of Canada, the CBSA and his lawyers yielded no results.

Steve Shand, a Florida man facing smuggling charges linked to the deaths of four migrants who froze to death during a blizzard in Manitoba last January, will stand trial on July 18.

Two people were arrested by the RCMP on human smuggling charges in Cornwall late last year.

Global News asked the RCMP headquarters, as well as their Ontario and Quebec divisions, the CBSA and U.S. Customs and Border Protection, for human smuggling data.

Border security is a shared mandate between the CBSA and RCMP. The CBSA is responsible for enforcing legislation at designated ports of entry, while the RCMP enforces the law between those ports.

The Ontario RCMP said in 2022 in Cornwall, they apprehended 142 people attempting to be smuggled southbound into the U.S., and just seven heading north into Canada. The disparity is likely due to Roxham Road still being operational in 2022.

From January to April 2023, Cornwall RCMP say they have intercepted 20 southbound human smuggling occurrences, with an unconfirmed number of people involved.

The CBSA said between 2016 and 2022, they opened 386 human smuggling criminal investigations across Canada. The agency laid charges in 167 of them.

The CBSA initially agreed to provide the entire 10 years of human smuggling statistics but later declined “after further review.” It also declined to break down the statistics by year.

Each of the other agencies refused to provide data.

The CBSA also would not comment on the case of the Iordaches, a Romanian family facing a deportation order who were one of the two families who died in the St. Lawrence River in March. Instead, it provided a general statement on removal orders.

“All individuals who are subject to enforcement action by the CBSA have access to due process and procedural fairness. Once individuals have exhausted all legal avenues of appeal and due process, they are expected to respect our laws and leave Canada or be removed,” the statement said.

Migrant numbers at the U.S.-Canada border are increasing

Experts worry that as the number of migrants heading to the U.S.-Canada border increases, many will resort to human smugglers and risky modes of transport.

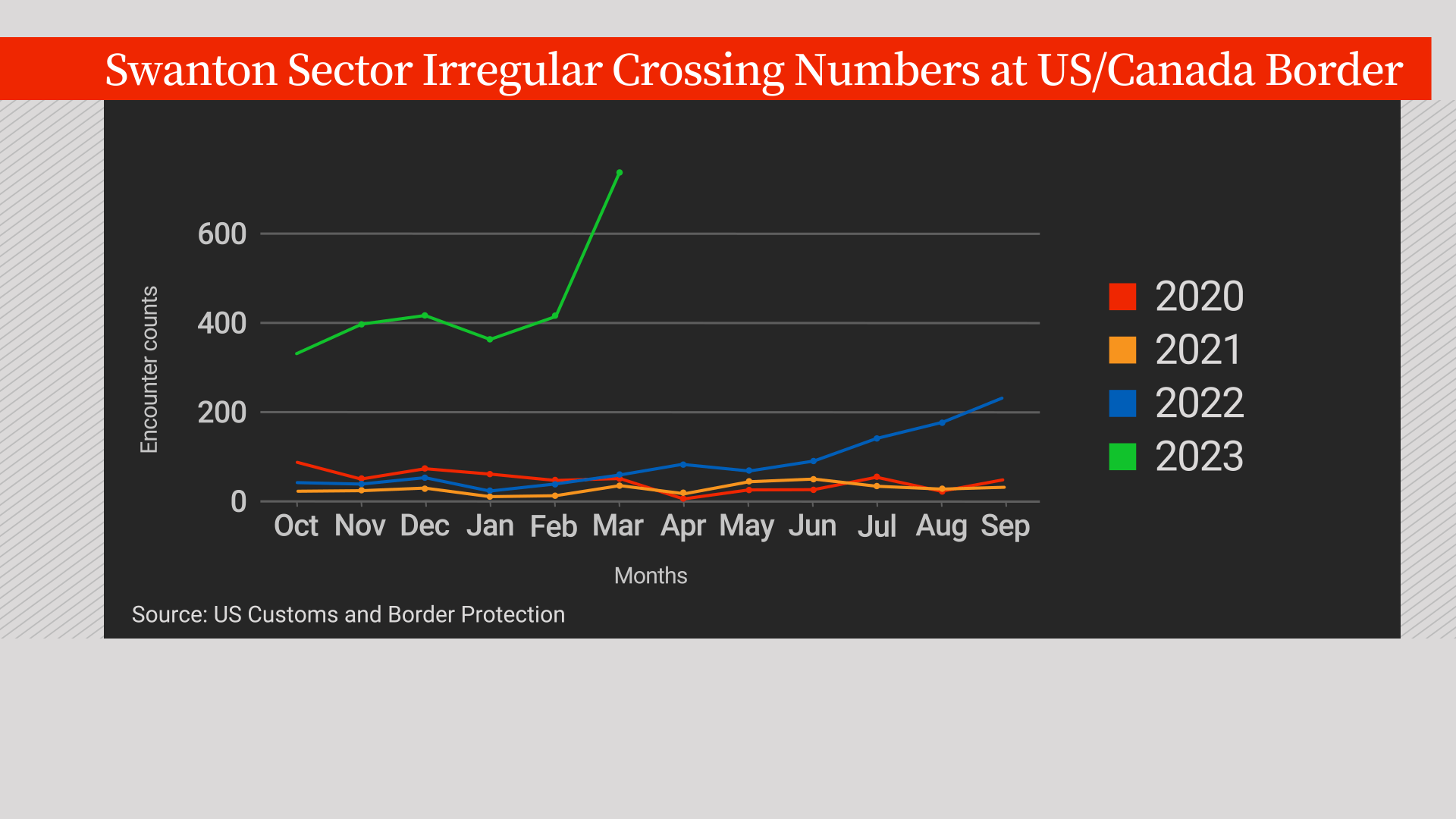

Just six months into 2023, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) has recorded 2,670 “apprehensions or encounters” with migrants crossing from Canada across the Swanton Sector – the most popular crossing point on the U.S.-Canada border. That’s more than double (1,065) what was recorded in 2022 as a whole.

The CBP defines an apprehension as “the physical control or temporary detainment of a person who is not lawfully in the United States, which may or may not result in an arrest.” An encounter is those who are either apprehended and expelled from the country or apprehended and allowed to go through routine removal proceedings.

January’s total of 367 surpassed the preceding January apprehensions for the past 12 years combined, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

Canada’s data is harder to track due to its convoluted border management system.

Statistics from the Immigration and Refugees Board (IRB) show that irregular border crossings into Canada leading to refugee claims have been climbing for months. In the first quarter of 2022, there were 2,772 claims from irregular border crossers. By the fourth quarter, that number had almost tripled.

The RCMP intercepted 39,611 irregular migrants entering Canada in 2022. Between Jan. 1 and March 31 this year, that number was already at 13,748.

Quebec RCMP noted a “significant increase” in southbound activity in recent months, but a “noticeable decrease” in northbound traffic following the closure of Roxham Road.

“Most times, these individuals that are interdicted by our officers are legally in Canada, sometimes having arrived in Canada days earlier through Toronto or Montreal airports,” a Quebec RCMP spokesperson said.

Experts worry that with the increase in numbers, and without the unofficial border crossing at Roxham Road, asylum seekers will attempt riskier crossing methods – leading to more deaths.

“People’s situations are not going to change just because Canada closed the border,” refugee and immigration lawyer Maureen Silcoff says.

“They still need a safe haven. That’s the dangerous part because we know people will fall prey to agents or smugglers who will put people in perilous situations.”

Not enough time has passed since the closing of Roxham Road for its impacts to be gauged, Silcoff says, but she believes other routes will likely open up along the border. She believes that the smuggling industry will “easily adjust itself” to Canada’s new rules, but “more people will be in harm’s way.”

“The government can still invoke public policy exemptions to mitigate that loss of life,” she says.

“People’s need for protection will not change.”

'The RCMP … do a substandard job’

Sundberg says the increase in the number of travellers attempting land border crossings is a reflection of global instability: a migration crisis, namely, owing to ongoing global conflicts.

Canada’s border services, he says, aren’t equipped to deal with it.

“Two organizations in many regards are addressing the same issue – to monitor irregular migration and protect our borders. It’s inefficient. The RCMP are our defacto border control, and they do a substandard job of it. They don’t have the bodies or the resources to do a better job,” he says.

To improve Canada’s border security, Sundberg says, Ottawa should consolidate border security and migration control under one agency: the CBSA. Officers should also be specially trained in geopolitics, migration and the psychology of human smuggling.

Sundberg also says there should be more officers abroad, especially at high commissions, and a closer working relationship with Homeland Security to understand human-smuggling patterns. Given that airport border security is now largely automated, the CBSA could pull its staff from there to support these new roles, he says.

“We have control of our airports, but we definitely don’t have control of our land borders.”